Some Notes on Taking Notes

A quick browse through my Instagram account and you might guess that I take notes. Lots of notes. And you'd be spot on! For this reason, I suppose, I am often asked the question, "How do you do it?!" Now while I don't think my note-taking strategy is particularly special, I am happy to share! I'll preface the information by stating what you probably already know: I LOVE to write.* I am a very visual learner and often need to go through the physical act of writing things down in order for information to "stick." So while some people think aloud (or quietly),

I think on paper.

My study habits, then, are built on this fact. Of course not everyone learns in this way, so this post is not intended to be a how-to guide. It's just a here's-what-I-do guide.

With that said, below is a step-by-step process I tried to follow during my final years of undergrad and first two years of grad school.**

Step 1

Read the appropriate chapter/section in the book before class

I am an "active reader," so my books have tons of scribbles, underlines, questions, and "aha" moments written on the pages. I like to write while I read because it gives me time to pause and think about the material. For me, reading a mathematical text is not like reading a novel. It often takes me a long time just to understand a single paragraph! Or a single sentence. I also like to mark things that I don't understand so I'll know what to look for in the upcoming lecture.

I own several PDF texts too, though I prefer physical books. (It's hard to snuggle up with your computer at night.) But I like to mark up those PDFs as well. I use the notation tools available in Apple's Preview app for this.

STEP 2

Attend lecture and take notes

This step is pretty self-explanatory, but I will mention this: I write down much more than what is written on the chalkboard (or whiteboard). In fact, a good portion of my in-class notes consists of what the professor has said but hasn't written. And perhaps now is a good time to tell you...

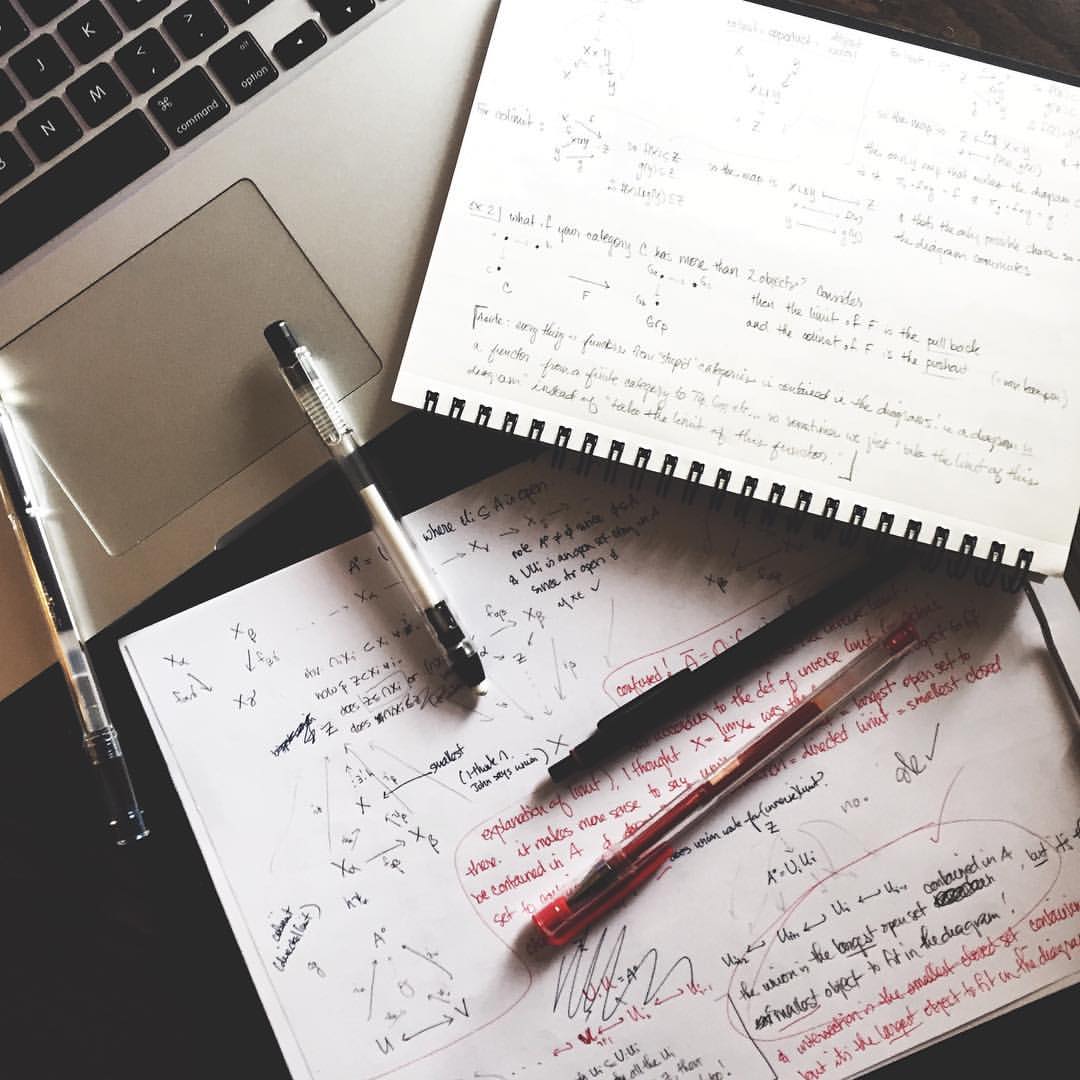

- I used to take lecture notes with a Lamy fountain pen, then I moved on to this gel pen and also this one. Now I use a mechanical pencil (see next bullet). But I always have one red and one green pen with me. I use green for questions ("What did the prof just say?" "What does this mean?" "How is this even possible?") and red for things I really want to remember. ("Oh that's what she meant." "Here's the key!" "Of course it must be possible!") I use this green/red scheme in my books and PDFs, too.

- While taking notes at home (step 3 below) I use a Rotring 600 drafting pencil. And I love dark, silky-smooth fine lines, so I use 0.5mm 3B grade lead. To date, my favorite is this one.

- For years I took notes on lined paper, but Jeremy Kun convinced me otherwise. Nowadays lined paper makes me cringe. Instead, I use blank white printing paper for my in-class and scratch notes (I always have a clip-board with me) and these spiral-bound, unruled Maruman Mnemosyne notebooks for all other notes*** (pictured above; also see step 3 below).

- I don't use LaTeX for my everyday note-taking. (But I used to type up my homework solutions in LaTeX.) While I do enjoy typesetting math, it can be time-consuming, especially when including pictures and diagrams. Plus, I like the feel of pencil-to-paper and, admittedly, the look of my own handwriting!

STEP 3

Rewrite lecture notes at home

My in-class notes are often an incomprehensible mess of frantically-scribbled hieroglyphs. So when I go home, I like to rewrite everything in a more organized fashion. This gives the information time to simmer and marinate in my brain. I'm able to ponder each statement at my own pace, fill in any gaps, and/or work through any exercises the professor might have suggested. I'll also refer back to the textbook as needed.

Sometimes while rewriting these notes, I'll copy things word-for-word (either from the lecture, the textbook, or both), especially if the material is very new or very dense. Although this can be redundant, it helps me slow down and lets me think about what the ideas really mean. Other times I'll just rewrite things in my own words in a way that makes sense to me.

As for the content itself, my notes usually follow a "definition then theorem then proof" outline, simply because that's how material is often presented in the lecture. But sometimes it's hard to see the forest for the trees (i.e. it's easy to get lost in the details), so I'll occasionally write "PAUSE!" or "KEY IDEA!" in the middle of the page. I'll then take the time to write a mini exposition that summarizes the main idea of the previous pages. I've found this to be especially helpful when looking back at my notes after several months (or years) have gone by. I may not have time to read all the details/calculations, so it's nice to glance at a summary for a quick refresher.

And every now and then, I'll rewrite my rewritten notes in the form of a blog post! Many of my earlier posts here at Math3ma were "aha" moments that are now engrained in my brain because I took the time to blog about them.

STEP 4

Do homework problems

Once upon a time, I used to think the following:

How can I do problems if I haven't spent a bajillion hours learning the theory first?

But now I believe there's something to be said for the converse:

How can I understand the theory if I haven't done a bajillion examples first?

In other words, taking good notes and understanding theory is one thing, but putting that theory into practice is a completely different beast. As a wise person once said, "The only way to learn math is to DO math." So although I've listed "do homework problems" as the last step, I think it's really first in terms of priority.

Typically, then, I'll make a short to-do list (which includes homework assignments along with other study-related duties) each morning. And I'll give myself a time limit for each task. For example, something like "geometry HW, 3 hours" might appear on my list, whereas "do geometry today" will not. Setting a time gives me a goal to reach for which helps me stay focused. And I may be tricking my brain here, but a specific, three-hour assignment sounds much less daunting than an unspecified, all-day task. (Of course, my lists always contain multiple items that take several hours each, but as the old adage goes, "How do you eat an elephant? One bite at a time.")

By the way, in my first two years of grad school I often worked with my classmates on homework problems. I didn't do this in college, but in grad school I've found it tricky to digest all the material alone - there's just too much of it! So typically I'd first attempt exercises on my own, then meet up with a classmate or two to discuss our ideas and solutions and perhaps attend office hours with any questions.

As far as storage goes, I have a huge binder that contains all of my rewritten notes*** from my first and second year classes. (I use sheet protectors to keep them organized according to subject.) On the other hard, I use a paper tray like this one to store my lecture notes while the semester is in progress. Once classes are over, I'll scan and save them to an external hard drive. I've also scanned and saved all my homework assignments.

Well, I think that's about it! As I mentioned earlier, these steps were only my ideal plan. I often couldn't apply them to every class -- there's just not enough time! -- so I'd only do it for my more difficult courses. And even then, there might not be enough time for steps 1 and 3, and I'd have to start working on homework right after a lecture.

But as my advisor recently told me,"It's okay to not know everything." Indeed, I think the main thing is to just do something. Anything. As much as you can. And as time goes on, you realize you really are learning something, even if it doesn't feel like it at the time.

Alright, friends, I think that's all I have to share. I hope it was somewhat informative. If you have any questions, don't hesitate to leave it in a comment below!

*Truly. I've kept a journal since I was seven years old!

**Typically, the first one or two years of grad school are much different than the latter years. (I've just finished my third year.) Once the written qualifying exams are over, less time is spent in the classroom and more time is spent on research. For that reason, my current note-taking strategy doesn't follow this four-step scheme. See next footnote.

***A word of clarification: Up until several months ago, I would rewrite my lecture notes on loose-leaf paper. But these days I don't rewrite my lecture notes because I don't take many classes! (That's just the nature of graduate school.) I do, however, learn things on my own (guided by my advisor) and therefore still take lots of notes. And that is what I use those black, spiral-bound Maruman notebooks are for.